Abingdon is a small town in rural Oxfordshire that is tucked into the confluence of the River Thames and the River Ock. It is a pretty town of medieval Abbey ruins, half timbered houses and a stone bridge and has a strong claim to be oldest continually inhabited settlement in England with archaeological evidence of an ongoing population here from the Iron Age onwards. Unlike other places which have periods of abandonment, here one period of history seems to blend into the next – Iron Age to Roman, Roman to Saxon and on into Medieval period.

Yet in the name of the place there is a bit of a mystery. The name is of Old English in origin and seems to mean ‘Hill of a man named Æbba”

This then generates two questions. Who was Aebba and where is the hill?

You see, Abingdon stands in a valley. It is right next to the River Thames and certainly not on a hill.

So how did the town come by its name? To try and answer this we have to delve into legends, myths and what exist of records relating to the founding of an Abbey in this town as well as to the earliest years of Anglo-Saxon Britain.

Amongst the early manuscripts and charters recorded by the monks of Abingdon several survive in the volumes of the Cotton Manuscripts now in the British Library. Cotton was a 16th to 17th century collector whose Library preserved many of the early documents that are critical evidence in piecing together these earlier years. Many of the Cotton Manuscripts were named after Emperors. One of the manuscripts named after Claudius -Claudius C tells us about the founding of an Abbey at Abingdon in the 7th century.

The Abbey was founded by a certain Hean under the supervision of a sub king of Wessex called Cissa who was uncle to Hean. The Abbey was founded circa 680 A.D. The Abbey was later sacked by the Vikings but then in 954 King Eadred appointed Æthelwold, as abbot. He was a very significant figures in the English Benedictine Reform, and so under his leadership Abingdon became one of the most important Abbeys in England. Here it was that the Chronicle of the Monastery of Abingdon was written in the 12th century. Most of what we know including the Cotton manuscripts comes originally from that chronicle.

The chronicles record the history of the Abbey very well from the 10th century but the original founding of the abbey and how the town got its name requires us to dig a bit deeper.

The Treachery of the Long knives

There is a tale recorded in 9th century Historia Brittonum attributed to the Welsh historian Nennius and later elaborated upon by Geoffrey of Monnouth in his 12th century Historia regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain). The historical reliability of these accounts is debatable – particularly in the case of Monmouth’s work which is basically historical fiction. Never -the-less given the paucity of documentation these are all we have to go on for some of the event. The sections relevant to Abingdon relate to the so called ‘Treachery of the long Knives’ or the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ which was an occasion when Hengist and the first Saxon lords to come to Britain were invited to dine with Vortigern, High King of Britain. The Saxons were invited in peace but each took a knife hidden upon them. When the British were drunk, Hengist called on his men to pull out their blades and the result was the massacre of the nobles and leaders of the British. Vortigern was spared both as he was married to Hengist’s daughter and probably in order to be ransomed.

The traditions of the founding of the Abbey of Abingdon, mostly recorded in the medieval period contain a story that a young man survived the massacre and fled north from the scene of the atrocity (Stonehenge) and up the Thames valley. There he retreated to a hill which became a holy site and according to the legend the beginnings of a monastery. The man’s name was Aebba and so it was that the hill upon which he created the hermitage became the ‘Hill of a man named Æbba”

Another account in another manuscript about the founding of Abingdon Abbey talks about a monastery being founded by an Irish monk called Aben who came to the area “before the Saxons came to Britain”.

Whether our man is a British nobleman or an Irish Monk we have a man called Aebba or Aben coming to the area and setting up a retreat or monastery around the time the first Saxons are coming to Britain – so some time in the 5th century.

What about the Hill?

So if we have the origins of the Aebba or Aben in Abingdon, what then of the hill? Where did that come from? Abingdon lies on a flat valley bottom along the Thames with no obvious hill close at hand.

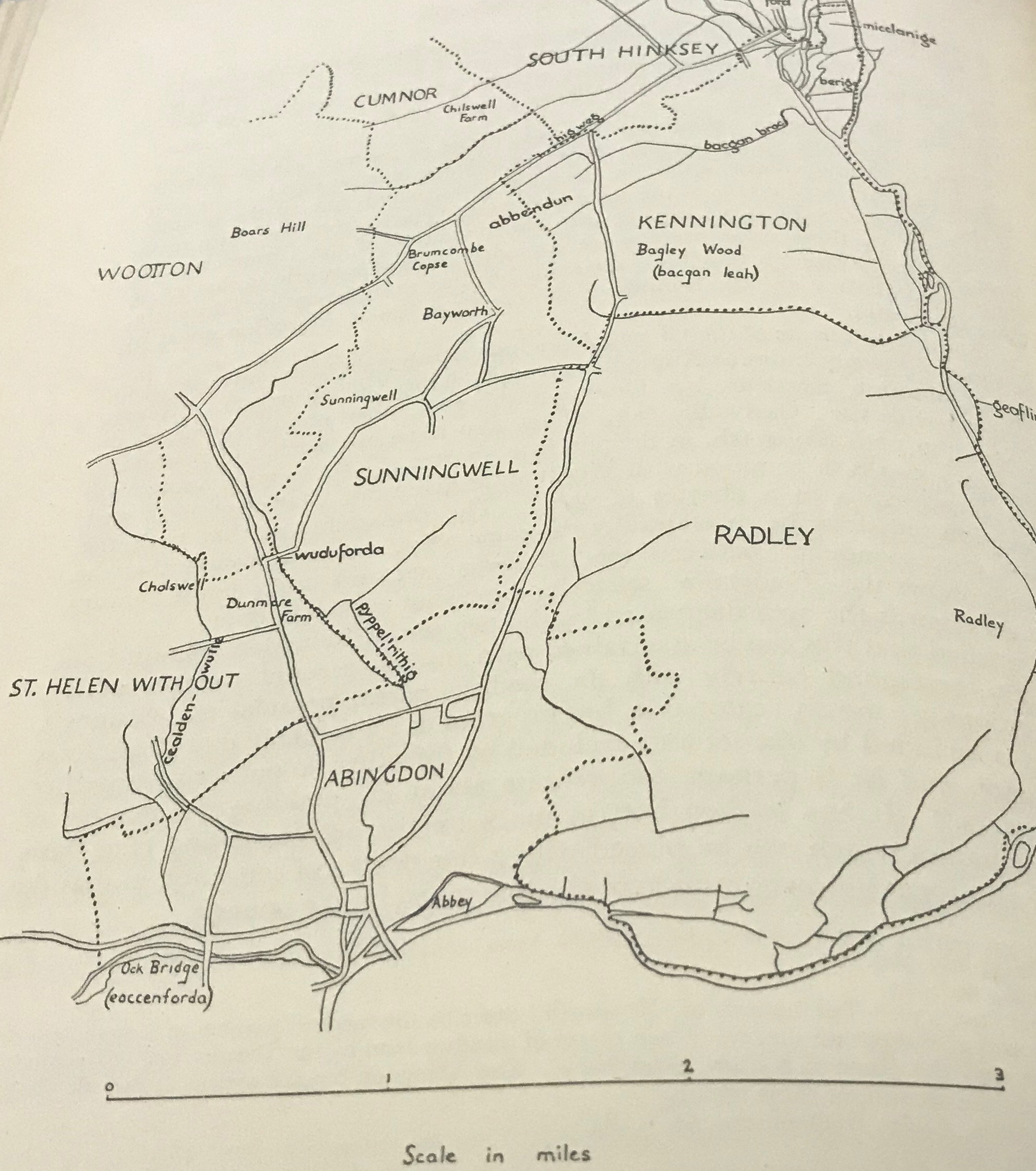

In the Cotton Manuscripts (Claudius C) there is talk of land being granted to the monastery officially in the form of a deed. The deed contains the bounds of the land in the form often used in these documents – it literally describes a particular stream, a hollow, a road and a place where two parish boundaries meet at a hill. That hill is called Abbendun. Historians have examined this description and located the spot described. The map below is a suggested location in Biddle, M, Lambrick, G, and Myres, J N L, 1968 The Early History of Abingdon,

Berkshire, and its Abbey, Medieval Archaeology XII, 26-6.

It is now believed that a hill once called Abbendum can be identified as Boars Hill some miles north and west of Abingdon. I visited the hill recently. Apparently in the last century or so the formerly bare hill side which afforded great sweeping views across the countryside has become a popular location for building on and along with the buildings have come trees. Thus it is difficult to both see the hill and get an idea what it would have one looked like.

We did locate a mound built on Boars Hill to allow views across the area but alas the view is blocked by trees! It is still pleasant area for a walk on a walk summer’s day however.

So what happened?

If a man called Aebba came to a hill now called Boar’s Hill in what is now Oxfordshire and made a monastery there and left his name as the name of the hill – Abbendun, how did that become the name of a town a few miles away? This raises another question. What in fact was the settlement called originally?

There is a manuscript (MSS 933) at Trinity College Cambridge which contains entries about the year 688 which refer to the foundation of the Abbey at Abingdon.

This talks about Hean under Cissa’s command bringing the abbey of Abbendun down from a hill to a village called Souekesham.

Can we be sure that Abingdon was once called Souekesham? Souekesham would mean the dwelling of a person called Soueke. There is another other place name in the area with a similar origin – the modern day Seacourt (Old English Seuecurda) – so maybe evidence of a couple of locations named after the same figure. Maybe Soueke was a 5th century Saxon who settled in the area. We know from the archaeology of the Saxton Road side at Abingdon that this place was settled by Saxons as early as the mid 5th century. the Thames river provided an easy route for Saxons to migrate into the heart of Britain and many Thames valley locations show early evidence of this settlement.

The evidence of St Helens.

Cotton Claudius C and Cotton Vitellius A tell of the founding of not just a single monastery but a joint monastery and nunnery. Hean was to found the monastery and his sister – a certain Cilla a nunnery. The name for the site of the nunnery was Helenstowe. Cilla is recorded as having made a small black cross of iron made (from one of the nails from the true cross) and was to be buried with it. Aethelwold’s monks digging in the area of what today is called St Helen’s church in Abingdon were supposed to have found the cross so it seems that Cilla built here nunnery on eth spot of what today is the church of St Helen’s and Hean his monastery or Abbey were the medieval Abbey would later stand.

Putting it all together

So the story might go like this – a man called Aebba fleeing from the masacare of the long knives, or alternatively an Irish monk called Aben come to a remote hill in Oxfordshire in the 5th century and found a retreat or monastery. In time it is named after him. Thus Abbendum is named.

Two centuries later a brother and sister are given instructions to found a joint monastery and a nunnery in the area. There is already perhaps a religious community at Abbendum of sufficient significance for Hean to want to use the name. Yet the location is not ideal. A small river side village nearby called Souekesham is far better suited. There is a river for a mill and fish aplenty. There is space for both his sister’s nunnery and his monastery there.

So the existing name was taken and in time Souekesham as a name passed into legend and was forgotten – preserved only in an ancient manuscript in the early records of the Abbey.

Souekesham took the name Abbendum which in that form or as Abingdon is now the name it has been known as for over 13 centuries.

I find these origin stories of places fascinating. Often we walk about seeing names of places and are unaware what the story is behind them. What’s in a name? Often quite a lot.