The defeat that shook the Victorian World

The Anglo-Zulu war of 1879 started with a great defeat for the British invaders. On the 22nd January 20,000 Zulu’s overwhelmed a force of 1800 British and allies on the plain beneath the mountain of Isandlwana and destroyed it. An entire battalion of British Infantry was wiped out to the last man. It was a defeat that stunned a Victorian Britain which was used to victory and conquest.

This battle, along with the stubborn and heroic defence of Rorke’s Drift the following night by the British garrison there, has always been of interest to me as it seems to exemplify the heights of human heroism (exhibited by both sides) coupled with the depths of folly and horrors that only war can bring.

Background

The origins of the conflict with the Zulus in 1879 have strange parallels with the conflicts in the gulf and the Middle East. In fairly recent times the US and allies’ interventions in the gulf have been seen by some as spurred on by a concern about access to oil. Whether that is true or not the British government in Cape Town back then did not take much interest in the interior of South Africa and much less Zululand until diamonds and other resources were discovered there. Suddenly in the 1870s efforts and policies were introduced aimed towards confederation of the various colonies under a strong British rule.

Amongst the territories brought under the British Crown was Natal and the Boer’s homeland of Transvaal. The Boer’s main enemy and rival was the strong and powerful independent nation that had arisen under Shaka Zulu in the 1830’s. A nation that could put 25,000 warriors in the field was a threat to the security of Transvaal and so ultimately all of South Africa. Or at least THAT is the way that Sir Henry Frere – the British governor – looked at it.

Frere sent Cetshwayo – the Zulu King a series of demands and ultimatums insisting that he disband his army and allow a British governor into his capital Ulundi. Frere knew that Cetshwayo would never agree to that and when the Zulu King declined his demands, the British general Chelmsford was ordered to invade.

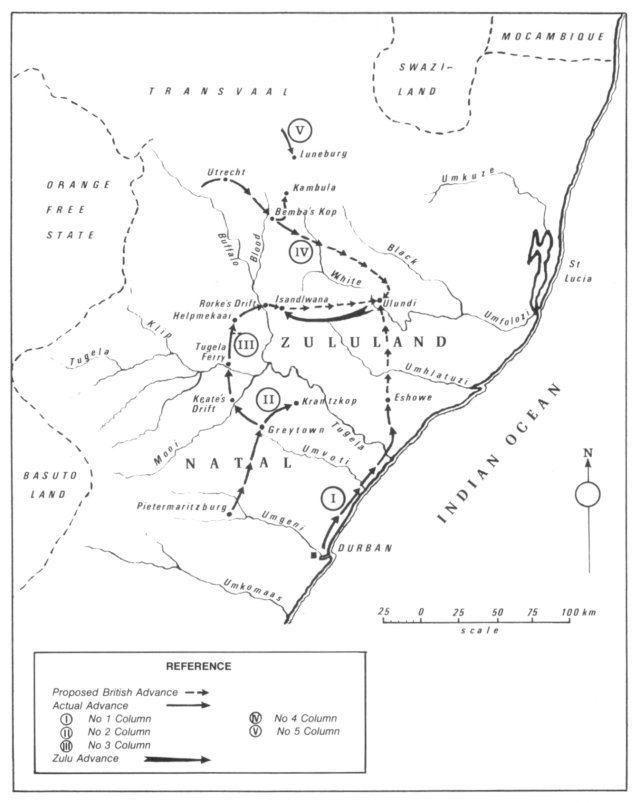

Chelmsford’s original plan envisaged splitting his army into 5 columns which would invade and converge on Ulundi. Chelmsford himself accompanied the central columns (II and III). They marched to the mission station at Rorke’s Drift and on 11th January began the invasion. It would have been better to have waited a few weeks as in January there was heavy rain and as a result moving a large army with baggage and artillery would take a long time. However Frere was eager to have the matter resolved and so the British went in. The result was that it took many days for the central column to assemble fully inside Zululand at a base Chelmsford has established beneath an odd shaped mountain called Isandlwana.

What Happened

Cetshwayo heard of the invasion soon after it had begun and on 17th January ordered 24,000 men to move towards Isandlwana, although some 4000 splitt off to move towards Column I. On 21st January the Zulu Impi had arrived near the British camp. Chelmsford’s scouts had seen it approach but could not fix its location precisely so on the 22nd Chelmsford decided to take half his force away on a march to try and locate the enemy.

This left Major Pulliene – a staff officer and administrator in the base with his 1700 men. Chelmsford had refused to order the camp to form into a laager – a reinforced camp with wagons around the outside, trenches and thorn bushes pulled into impede attack. He did not feel it was neccesary and was scathing of threat posed by the Impi.

This mistake would prove to be costly for the Zulu commander had out maneouvered Chelmsford and whilst the British general was chasing around trying to locate him, the Impi moved forward in redinness to fall on Pulleine.

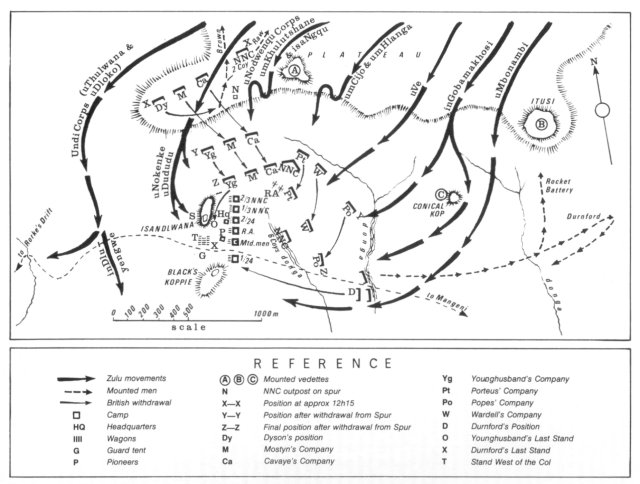

The crunch happened when a patrol of Natal mounted trops attached to the British command moved out of the camp to scout some valleys to the north east. There in a valley within a couple of miles of the camp was the entire Zulu army. As one the zulus rose up and attacked the fleeing horsemen and followed them up and out onto the plain.

Pulleine formed the 24th Foot up into firing lines and the British Infantry began puring volleys from their Martini Henry Rifles into the enemy ranks. The zulus fell in droves but still came on- massing and waiting to charge. Actually the redcoats held the vast numbers away for a long time but then something went wrong.

Around 1.15 pm that day the Natal irregular companies out on the British right wing were outflanked and fell back. More or less at that moment Pulleine was ordering the Regular companies to pull back to shorten their line. There was also a shortage of ammunition reaching the forward companies. There was a vast supply in the camp but for some reason these were not being handed out quickly enough. A combination of these factors meant that the previously pinned Zulu Impi was able to charge the British line.

Gaps appeared in the companies, then the gaps widened as the warriors surged through them. In a matter of fifteen minutes the Zulu army overwhelmed the British and the wings of the Impi swung into deny escape to all save a lucky 80 or so men. The colour party with the regimental and the Queen’s flag wrapped the flags around the chests of two officers who made a bid to reach the Buffalo river. Their bodies were later found in the river, where they had fallen.

It was all over in a flash and the British had suffered a huge defeat.

Aftermath

Cetshwayo had ordered that the Impi should NOT invade Natal and should stop on his side of the border. However a few thousand Zulus who had not fought at Isandlwana decided to attack the British base at the mission station of Rorke’s Drift. Throughout the night of the 22nd to 23rd January they led repeated attacked against a single company of British that fortified it. 11 Victoria crosses would be handed out for the bravery of officers and men on the 24th Foot stationed there. The Zulus broke of the attack in the morning.

Cetshwayo had missed two opportunities to inflict a decisive defeat. His Impi had not attacked the column under Chelmsford, nor captured Rorke’s Drift. As a result, the war was not yet over.

News of the defeat at Isandlwana reached London on 11th February and caused an uproar. It literally stunned the nation and even the Queen demanded to know why her soldiers were fighting the Zulus. It is small wonder then that the subsequent news of Rorke’s drift arriving hot on the heels of the disaster was greeted with enthusiasm.

Nevertheless the defeat lead to a calling off of the of the January invasion. It would be June before the British army would be in a state to resume the war and July before the Impi was defeated at the battle of Ulundi. Cetshwayo was captured by the British in August but, perhaps in recognition of the bravery of his army, was treated pretty well, became something of a celebrity in London and was allowed to live on a pension for the rest of his life. His Kingdom, however, was absorbed into the British Territory of South Africa.

So then, a terrible battle and a tragic outcome for a brave warrior people. It remains a dramatic moment in history.

In Tomorrow’s Guardian, Edward Dyson – a officer in the 24th, is believed perished in the battle. Tom and his companion Septimus travel back in time to rescue him and bring him to the present day.

Find out more about Tomorrow’s Guardian as well as listen to an account of the battle and the rescue of Edward here:

http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/tomguard.html

Related Articles

No user responded in this post