One of the more well known battles between the Saxons and Vikings was the Battle of Maldon. This is due in part to the existence of a poem from soon after the battle that tells us about who took part and what happened. It is also one of the few battles from the time where we are reasonably certain where it took place.

The Battle of Maldon was fought on the 10th of August in 991 near the small town of Maldon beside the River Blackwater in Essex. It took place during the reign of the weak king, Aethelred the Unready. What is interesting is that this battle and its aftermath show the two main approaches to dealing with the Vikings. Some leaders would fight them and if successful this approach would often force the Vikings to come to terms and make peace for a while. The other approach was to bribe them with money or land. This might work and save lives in the short term BUT it could mean the danes felt that since threats had worked before why not try again. The Saxon leader at the battle favoured resistance and we shall see what happened.

The battle occurred during the years of Viking raids and invasions that raged on during the 8th to 10th centuries. Maldon was a coastal town and so vulnerable to attack. It had been fortified but its wealth still made it a target for the Vikings who had moved on there after attacking Ipswich. These raids on the east coast were costly and it seems that the local Saxon lord was Earl Byrhtnoth determined to try and engage the Vkings in a pitched battle in an attempt to destroy the host.

The Battlefield

Earl Byrhtnoth having heard of the Viking raids called out the local Fyrd (the militia which would defend the local area ) and along with his huscarls (personal troops) his thegns (lords) led the English against the Viking invasion.

Initial deployment

It is thought that the armies had perhaps 2000 men each (really we don’t know for certain).

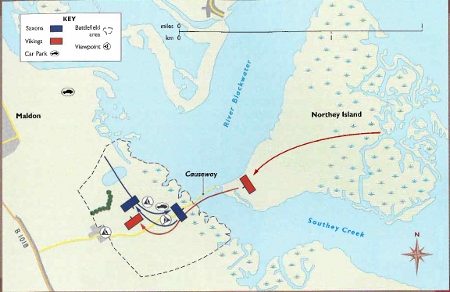

The Vikings had chosen not to directly assault Maldon (which would mean attacking the fortified port) but had landed in the safe anchorages and various channels of the estuary and then assembling on Northey Island had move towards the causeway which connected it to the main land via a causeway. The Saxons moved to the end of the causeway At the start of the battle the causeway was flooded and so what occured was a stand off with the two armies hurling abuses and challenges.

The Battle starts

Initially a few Saxon warriors held the causeway and denied the Vikings passage but then Byrhtnoth ordered the army to pull back and permit the enemy to cross. This is unlikely to have been good sportsmanship or a sense of honour. Byrhtnoth wanted to destroy the Vikings and so, possibly fearful they would just get in their ships and leave, he allowed them onto the main lands.

The battle then proceeded in a fairly standard manner with an exchange of arrows, slingstones and javelins. Then the main bodies closed and the push and shove of the shield wall ensued. It may be that the Saxons were doing OK until something unexpected happened. Byrhtnoth seems to have believed that an enemy leader was challenging him and stepped forward to engage in one to one combat. The Vikings fell upon him and cut him to pieces.

Once the leader was dead the Saxon Fyrd turned and fled. Byrhtnoth’s household troops and retainers fought over the body of their lord until slain but after his death the battle was over in moments.

The Aftermath.

The battle having ended in an Anglo-Saxon defeat, the Vikings went on to pillage Maldon. After the battle the Archbishop of Canterbury advised King Aethelred to follow the other policy and to try and buy off the Vikings rather than fight them. The King agreed and as a result a payment of 10,000 pounds of silver was handed over as Danegeld. The idea was that the Vikings would not come back but year after year return they did. Ultimately, despite English resistance, a Viking king would sit on the throne – Canute and the Vikings would rule England for 25 years.

A statue of Byrhtnoth in Maldon

The Poem

Fragments of an account of the battle probably written soon afterwards still survive today. The poem is embellished by proud boasts and accounts of the bravelry of the Saxons in much the same way that the poem Y Goddodin tells of the attributes and abilities of the defeated British at the earlier battle of Catreath in c597. So what we have is a piece of propaganda. Yet it does give us something of an outline of the battle as well as include references to some snapshots of the action that help us understand the weapons used.

My own historical fiction, The Amber Treasure, is set during the late 6th century and includes an account of the battle of Catreath.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post