On May 1, 1851, the Great Exhibition opened in the Crystal Palace in London. It was spectacle of such awesome sight and splendour that no one visiting it would have ever seen anything like it before. It was the model that the World Fairs of the future would be based upon. It was entirely an idea dreamt up by Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert. Europe and Britain in 1851 was at peace. The terrible Napoleonic wars were a distant memory and the horrors of the Crimea was two years into the future. Britain was entering the height of its Imperial age – a might driven by the engines of industry. It was this might and this industry that Albert planned to show the world.

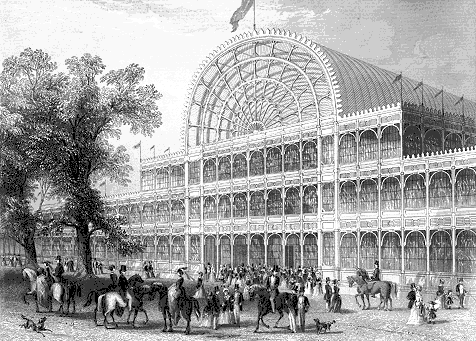

The commission in charge of the exhibition held an international competition to design a building for the exhibition. the winning bid was that of Joseph Paxton. He designed a huge greenhouse to house the displays. Construction work began on 1 August 1850 and involved more than 2,000 men. The building work involved thousands of sheets of glass. 1,000 iron columns, 2,224 trellis girders, 4,000 tons of iron, 30 miles of guttering and 202 miles of sash bar.

The commission in charge of the exhibition held an international competition to design a building for the exhibition. the winning bid was that of Joseph Paxton. He designed a huge greenhouse to house the displays. Construction work began on 1 August 1850 and involved more than 2,000 men. The building work involved thousands of sheets of glass. 1,000 iron columns, 2,224 trellis girders, 4,000 tons of iron, 30 miles of guttering and 202 miles of sash bar.

On May 1st 1851 exactly on schedule the exhibition opened to a London eager and keen to see the wonders within. The Queen herself opened the exhibition and visited on several occasions. At first the price was £3 for gentlemen and £2 for ladies. Their coaches were valet parked whilst they looked around. On the 24th May the price was drooped to just the a shilling a head and the population responded with unbounded enthusiasm. The travel agent Thomas Cook arranged special excursion trains. They came in their many thousands from all over the United kingdom and the world.

When I hear people today saying that they don’t plan to visit the London Olympics because “London is a long way a way” I treat that remark with the contempt it deserves. In 1851 people travelled hundreds of miles in slow coaches and trains. One old lady even walked, all the way from Penzance to visit it!

When they arrived outside they were treated to a true wonder of the world.

As they emerged from between the buildings, Tom saw a sight that took his breath away. Rising above the mature oaks and beech trees that populated Hyde Park was a colossal structure. Made of glass and steel, which caught and reflected the summer sun as it climbed the southern skies at their backs, Tom got the impression of a gigantic greenhouse. Indeed, in terms of style if not size, the building did look a little like the one his grandfather owned on an allotment a few streets from Tom’s house. He almost expected to see the old man pottering around with pruning shears. This, though, was not a greenhouse. This was a vast exhibition hall hundreds of metres long and so tall that Tom could see that its roof actually arched above one of the Park’s ancient oak trees. No wonder they called it the Crystal Palace, he thought.

From Yesterday’s Treasures (Young Adult Time Travel Novel)

But the building was only a taster for the great treasures they would see within.

The interior rose like a great cathedral above them, but whilst a medieval cathedral had arches and pillars of ancient stone, this edifice was made of vast steel girders and huge sheets of glass. A central nave ran the length of the building. Down each side were great alcoves above which a balcony projected and from which hung dozens of flags from all over the world: France, Britain, America – and many more that Tom could not recognise. As they walked around they found the place was divided into courts each with a different theme. The Indian Court was gaudily adorned with jewels, exotic fabrics and clothing, which Tom had seen ladies wearing in the Asian supermarkets in his own city. The China Court was full of ceramics, vases, oriental screens, and illuminated lanterns; whilst the Turkish Court was populated by hookahs, curved scimitars and a camel saddle. Not far away was a huge Celtic Cross. These items were surrounded and dwarfed by great machines which puffed and groaned as their pistons pumped up and down and hammers rose and fell.

“This is the height of the Industrial Revolution, Tommy boy,” Septimus said as they paused by one vast machine that was punching holes in steel sheets. “The power of this industry is giving all these nations an empire. But it is Britain that is becoming the super power of the Victorian age and whether you think that is right or wrong, the Brits of this day are not afraid to brag about it. To be honest it’s quite exciting, isn’t it?”

Albert had sent out invitations to the world to send their greatest and most splendid innovations. The response was awesome. There were some 100,000 objects, displayed along more than ten miles, by over 15,000 contributors.Half of the exhibits were from Britain and from the Empire. The biggest items of all was Stevenson’s massive hydraulic press that had lifted the metal tubes of the bridge at Bangor. There were examples of every kind of steam engine, including the giant railway locomotives. As the Queen put it in her Diary, ‘every conceivable invention’ could be seen

The American display headed by a massive eagle, wings outstretched, holding a drapery of the Stars and Stripes featured prominently Colt’s repeating fire-arms. The Russian exhibits were superlative and included huge vases twice the height of a man, furs, sledges and Cossack armour. The Swiss sent gold watches, the French sumptuous tapestries, Sevres porcelain and silks from Lyons, enamels from Limoges and furniture.

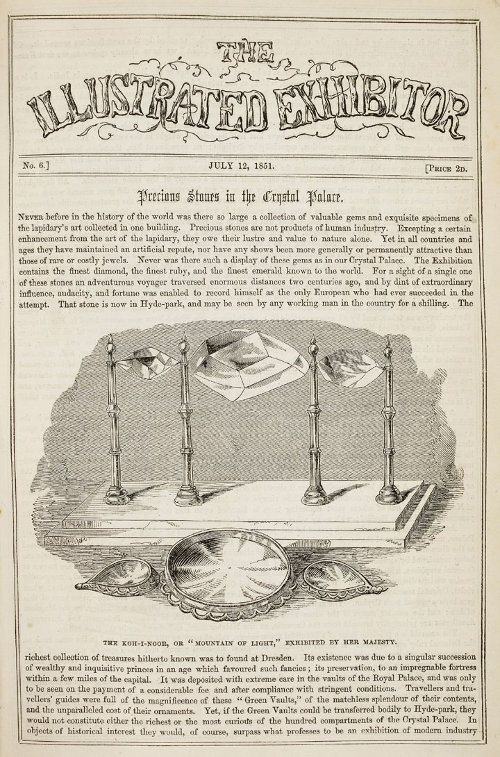

The single attraction that the crowds most eagerly queued to see was the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond. It was supposed to be of inestimable value, but most people found it dull and disappointing (It was not until it had been skillfully cut that its beauty emerged. It is now part of the Crown Jewels.)

Before the Exhibition had opened it was predicted it would make a loss. In fact when it closed, on 11th October, over six million people had gone through the turnstiles. It made a profit of £186,000, most of which was used to create the South Kensington museums that are still one of London’s great attractions.

The excepts are from my book Yesterday’s Treasures the second book in the Hourglass Institute series.