Christmas is coming in just a few day’s time. Along with the new year celebrations that follow it, it is in Britain the most important festival and holiday of the year. Families get together, give and receive presents, eat and drink and have a good time. Many businesses close down for almost 2 weeks and very little work gets done even in those places that are actually open. Unless of course they are pubs and restaurants!

In celebrating this time of year we recreate festivals that predate even the coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. For here it is deep winter. It is a time of long nights and short days. It is cold and dark and not a time to be out. This is a time to feast and create our own light and warmth and to look forward with hope to the return of the sun.

That at least is how our ancestors saw things. Christmas coincides with Yuletide – the ancient celebration that occupied midwinter. Here in England it was celebrated for a number of days running on from the 25th of December. At that time, under the old Julian calendar, December 25 was also the winter solstice. (Today it is 20th or 21st December of course).

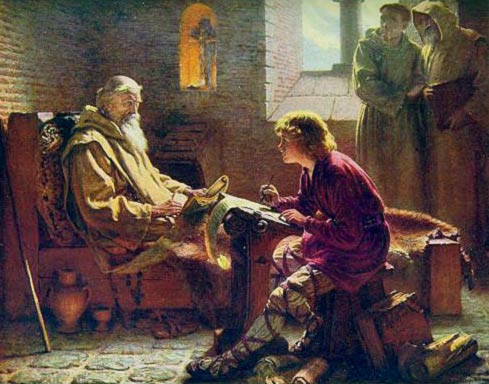

How do we know that the early Saxons celebrated Yuletide at this time? Well the 8th century scholar, Bede, tells us this in an essay he wrote on the Saxon calendar:

They began the year with December 25, the day we now celebrate as Christmas; and the very night to which we attach special sanctity they designated by the heathen mothers’ night — a name bestowed, I suspect, on account of the ceremonies they performed while watching this night through.

The very name for the months that straddled Yuletide -December and January – were considered “Giuli” or Yule by the Anglo-Saxons. The Anglo-Saxons celebrated the beginning of the year on December 25th,which they called Modranect”— that is, Mothers’ Night. This celebration was linked to the rebirth of ‘Mother’ Earth and the whole idea of ceremonies conducted at the time was to ensure fertility in the coming spring season.

As the Saxon gods of fertility were Freyja, who governed love and fertility and her twin brother Freyr then they may well have been linked to the celebrations.

Forget the Turkey – bring out the boar

It is probable that the feasts involved boars. Freyja and Freya were associated with the boar. This was the primary animal represented in Yuletide customs and indeed in Anglo-Saxon culture in general. It is mentioned in epic warrior poetry like Beowulf. A boar’s head may well have been sacrificed to appease the gods and the boar continued to ornament brooches, bowls and jewelry as well as more military objects for centuries.

The missionaries arrive

In the year 597 the pope at the time sent Augustine to England to try and convert it to Christianity. The process would take centuries but quite early on it appears that a decision was made to amalgamate the pagan festival of Yuletide with Christianity. Christmas as a festivity celebrating the birth of Jesus originated in Egypt sometime in the second century: here it took over a previous festivity, most likely the birth of Osiris. In Europe, Christianty encountered the Roman cult of Mithras. The 25th of December is now universally accepted as Mithras’ bithday. Mithras was an Iranic deity associated with Sun worship whose cult became so widespread in the Roman Empire as to become a serious threat for Christianity.

In 567 AD, in order to encourage the people to abandon pagan holidays, The Council of Tours declared the 12 days of Christmas to be a festival. Historically, the 12 days of Christmas followed-did not precede-December 25th. These dozen days ended the day before Epiphany (the coming of the Magi), which was celebrated on January 6th.

Christian influence, however, remained superficial until the time of the Norman Conquest. Rites included yule logs, use of evergreens, mistletoe, eating, drinking. Games such as leap frog and blind man’s buff were played at the time and actually originated in ancient fertility customs – an echo of mother’s night.

Gradually old Germanic Yule celebrations combined with nativity feasts, and the English Christmas began to take shape. Alfred The Great insisted that no business was done during the Twelve Days. By 1066 the Christianisation of England was complete and the Twelve Days were the main annual holiday.

So when we sit down to our Christmas lunch we recreate tradition that stretched back through fifteen and more centuries.

Merry Christmas and Happy Yuletide!