Royal Prerogative vs Parliamentary Freedoms

The Stuart period is the time when parliament increasingly flexed its muscles. The parliamentary structure of King, Lords and Commoners came into being in Tudor times. At this time the King still ruled the country and directed foreign policy. Tudor parliaments would at times petition and try and persuade the monarch of a particular direction of policy BUT they were rarely critical and given the character of Henry VIII, Mary and Elizabeth one can well understand a reluctance to take on them on!

Monarchs needed to go to parliament primarily to get money. The monarchy had income from three sources:

1. Large crown estates owned directly by the monarch.

2. Feudal dues from the bulk of the nobility.

3. Import duties (Called Tonnage and Poundage).

All of THAT income was the king’s by right. However at times of war and emergencies monarchs would go to Parliament who would then legislate ADDITIONAL taxation to raise funds that the the monarch needed. Parliament increasingly started to add restrictions and requirements linked to these grants.

James and Charles in particular objected to these restrictions – seeing them as an attack on their right as the God chosen King to rule. In particular they objected to any attack on Royal prerogative – areas they jealously guarded as the rights of the monarch:

The Right to go to war. (Technically still the Queen has to consent to going to war)

The right to choose alliances usually sealed by dynastic marriages.

The right to tax imports.

The struggle between Parliament and Monarch over these areas would be a feature of the next decade.

The Thirty Years war of 1618 to 1648 affects English Policies

In 1620 James was now 57 and was giving thought to the stability of the succession to his son Charles (later Charles I). Part of this would be the matter of the marriage of Charles – always a crucial part of alliances and politics.

James, his chief advisor, Villers (Lord Buckingham) and Prince Charles were all keen on a “Spanish Match” with the Spanish Infanta. This policy was put under threat by the Thirty Years war between (by and large) the Protestant nations of northern Europe and the Catholic nations of the south which included Spain.

James own son-in-law was a Protestant. This was Frederick V the Elector Palatine. In 1620 his opponent the Catholic Emperor Ferdinand II invaded Bohemia again and Spanish troops attacked Frederick’s lands in the Rhineland .

James decided he had to help his son in law and called a Parliament in 1621 to fund the war. The Commons did not grant sufficient money to carry out this war but at the same time demanded that James attack Spain. Â They also insisted that Prince Charles should marry a Protestant. Â Furious at this attack on his Royal rights, James tore up the petition and dismissed Parliament.

Charles and Buckingham Take matters into their own hands

IN 1623, frustrated by the obstruction by parliament and determined to carry through their policies, Prince Charles and Buckingham travelled to Spain in secret in an attempt to reach an agreement on the Spanish match. This attempt was an utter failure. The Infanta hated Charles at first sight. Furthermore the Spanish court insisted that Charles convert to Catholicism and imposed other intolerable criteria. When Charles and Buckingham finally returned home they tore up the agreement which finally went down well with the people.

A change of heart

In fact once home Charles and Buckingham completely changed tack. They started to pursue an alliance and marriage with France and urged James to go to war with Hapsburg Spain. IN 1624, Charles persuaded James to summon parliament and now all apart from James were in concord. Parliament was happy to take an anticatholic stance and seemed happy to finance the war and although James refused to declare war, Charles and Buckingham – now increasingly the power in the country believed they had secured support for their stance. This would have significant influence on the direction of Charles’ reign.

The end for James

Buckingham continued to exercise influence over Charles as James came to the end of his life. Â James grew ill in 1625 and died in March of that year. The funeral was magnificent and the public poured out an expression of sentiment and goodwill that showed that James had always managed to remain popular. After all he had managed to maintain peace throughout his 22 year reign.

Charles I becomes King

With the death of James, Charles inherited the throne. His first action – even before he was crowned was to conclude the French match that he had been negotiating since the failure of the Spanish venture. In haste and before Parliament could do anything to prevent it, he arranged a marriage in proxy to the French princess Henrietta Maria. Although Charles told parliament that he would not relax the anti-catholic laws he actually promised just that to the French King and even agreed to help the French suppress their own protestant minority, the Huguenots.

Charles gave further indication that that he was favouring a pro Catholic line by appointing as his personal chaplain a priest, Montagu, who was out spoke in his condemnation of many protestant beliefs. This perception in a protestant country that the King favoured catholism would strain relations with parliament and one day lead to many men backing parliament in a war against the king. But that is a tale for the next of these blogs.

Early Reign – Foreign policy and the Thirty Years War

Charles wished to aid his brother-in-law Elector Frederick V. The Hapsburgs were supporting the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II in the war against Frederick. The war was expanding and drawing in more and more nations. Charles wished to declare war on Spain and had decided to intervene directly in the war in Europe by sending troops. He went to parliament to ask for the funds to do this. Parliament did not want to send an army to Europe but preferred raids on Spanish treasure fleets and her colonies. To try and force the king’s hand they authorised only a small amount of money and furthermore restricted Charles right as king to levy taxes on imports (The so called Tonnage and Poundage duties).

Although the House of Commons passed a bill with these terms, Charles advisor, Buckingham in the House of Lords had it thrown out. Charles and Buckingham ignored the wishes of parliament and started up the war with Spain. The war went badly and by 1626 parliament were baying for blood and demanding Buckingham’s dismissal. Charles refused to comply.

Needing to fund the war which was draining funds badly, Charles started imprisoning anyone who refused to pay what he saw as his rightful duties. This caused outrage and in 1627 five knights who were so treated challenged the king’s actions in court. The court decided that it had no right to interfere with the traditional rights of the King to levy taxes. However in 1628 parliament forced through the petition of rights which specified that the King could not levy taxes without Parliament’s consent, impose martial law or imprison civilians without a fair trial. Charles agreed to this petition although in practice he did continue to levy taxes.

Decline of Buckingham’s influence and his death – Failure in expeditions to aid the Huguenots

Although Charles had agreed in his marriage treaty to help France suppress the Huguenots but he did not go through with this. Indeed between 1627 and 1629, alarmed by the growth of the French navy, Charles decided to go to war with France and help the protestant’s in France. Buckingham undertook naval actions designed to aid them including sending an expedition to seize Saint Martin-de-Re – a French strong hold near the Huguenot’s base. These expeditions were a total disaster.

As a result of these failings, his poor handling of the Spanish match in the early 20’s and the failure of the conduct of the Thirty Years war at large, Buckingham was hounded and pursued by parliament.

In August 1628, Buckingham was assassinated. The public rejoiced at the news. For Charles, devoid of funds to pursue them, Villers’ death also brought to an end the war with Spain and France. It did not however bring to an end the conflict between King and parliament.

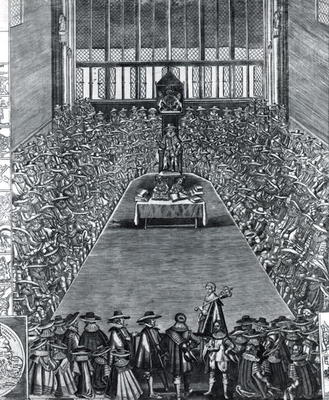

In January 1629 Charles opened Parliament with a speech on the tonnage and poundage issue. The Commons responded by saying he had broken the Petition of Rights by imprisoning one of their members, Rolle, for refusing to pay. Charles ordered the adjournment of Parliament. Determined to have their say, the members of the House of Commons actually held the Speaker in his seat until they had passed resolutions on rights and the tax issue.

Furious, Charles had eight members of the House including a significant figure for the future, John Pym, arrested and then dissolved parliament. These men were seen as Martyrs by the public.

Having failed to raise funds for war, Charles made peace with Spain and France and then set about ruling alone and without Parliament for 11 years. This period is known as the Personal Rule or the Eleven Years’ Tyranny.

Ruling without Parliament was quite acceptable in previous centuries but by the mid 17th century opinions were changing and perceptions of liberties and freedoms were growing. Charles still believed that he was answerable ONLY to God. Parliament and a good number of the people were beginning to feel differently. One day enough people would feel strongly enough about this to challenge the King. But not yet.

Next week – the Personal Rule.

Coming next week: 1630 to 1639

This article is one of a series connected with the release in August of the new paperback of The Last Seal my historical fantasy set during the Great Fire of 1666.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post