The English are by nature a sea faring race. After all they came to these islands in boats and ships – migrating from Germany and the low countries from the 5th century onwards. They came across the North Sea. Having settled in Britain and carved out England they seem to have in many cases lost much of the skills needed and it was the coming of the Vikings that re-awoke the need to constructs fleets again under Alfred the Great. But in the 6th and early 7th centuries the great migration was still under way. The English were building boats as evidenced by one of the great burial sites of the period – Sutton Hoo.

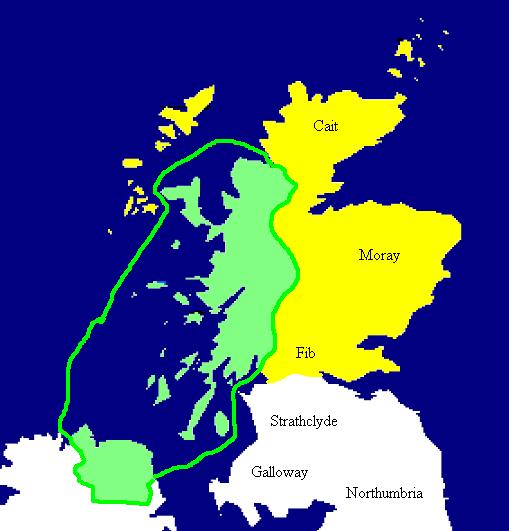

The Irish and Scots were also sailors. The 5th to 7th Centuries saw a large scale migration of Scots from Ulster accross the Irish sea to the west coast of what became Scotland. There they carved out a Kingdom – Dal-Riata the genesis of what would one day become Scotland. Dal-Riata was an archipelago of islands and peninsulas, lochs and lakes. The Scots needed ships and boats to get about.

The evidence

Evidence of what ships were being sailed at this time comes from three main sources – documentation, archeology and reconstruction.

Irish Currach and Corracles

This is a boat with a wooden frame, over which animal skins or hides were once stretched as opposed to wooden planks. The skins are sealed with tar to make it waterproof.

A Latin account of the 6th century voyage of St Brendan exists which contains an account of the building of an ocean-going boat: using iron tools, the monks made a thin-sided and wooden-ribbed vessel covering it with hides cured with oak bark. Tar was used to seal the places where the skins joined. A mast was then erected in the middle of the vessel . A sentence in the description sicut mos est in illis partibus (“as the custom is in those parts”),implies that the vessel as built in accordance with ordinary practice.

An Irish martyrology of this same period reports that the boat most commonly used there was made of wickerwork and covered with cowhide.

Here is a video of a man making the ancestor of the currach – the smaller river going corracles, big enough for 1 or 2 men. It is built from hazel branches over which hide is stretched.

The Life of St Columba tells us that the west coast and waterways of Scotland were teaming with vessels. There is a reference to one merchant who when he was lost at sea had a fleet of no less than fifty Currachs. In an other entry St Columba and his companions navigated a long way accross Scotland via lochs using a large vessels with a crew and a big mast and sail.

Wooden hulled vessels – long boats

Whilst the Irish- Scots had large fleets of hide covered Currachs and smaller corracles, the English were using vessels more like later Viking longships. WE know this from ship burial sites such as the Graveney ship found in the Kent marshes and Sutton Hoo. The great ship burial site of Sutton Hoo which was discovered just before World War II told us a lot about the ships that existed at the time. The ship its self had largely rotted BUT the outline was perfectly preserved:

The burial site contained a horde of Saxon treasures including a magnificent helmet. It is thought to belong to the burial site of King Redwald of East Anglia from the early 7th Century. Thus it is a perfect clue as to what wooden plank built Anglo-Saxon vessels of the period would look like.

In the 1980’s marine architect Edwin Gifford became interested in reconstructing Saxon sailing vessels. Their first replica was the Ottor, a half- size replica of the Graveney ship. They later built a half-size 45-foot replica of the Sutton Hoo ship, Sae Wylfing completed in 1993 in Southampton. Both reconstructions sail well and show that these ships were sail and oar sea going vessels.

The Anglo-Saxon longships were simpler and smaller than the great Viking vessels that would terrorise the coasts of Britain and Europe in a later time but of similar design. Probably what we see here is the ancestor of those later ships.

In reality an overlap between the Irish Currachs and the English Longships was likely and no doubt ships of both type would be seen in the North and Irish seas. Not just one or two but according to records in considerable number.

This article comes out of research for Child of Loki – the sequel to my Dark Ages Novel The Amber Treasure.

The Northern Crown Series Book TwoChild of Loki

|

|

A divided land … a divided family. The Battle of Catraeth has been won and Cerdic’s homeland is safe … but for how long? Soon Cerdic and his friends must go to war again – against the Scots and Picts north of Hadrian’s wall. He goes to help his country’s allies – the Bernicians – under their great

But what is Aethelfrith’s true design? How ambitious is he and how far will he go to fulfil

All Cerdic wants is to be left to live out his life in peace.

But Loki, it seems, has other ideas. |

Related Articles

2 users responded in this post

I think the Boyne coracle/currach was being actively used for fishing in the Boyne estuary in the early decades of the 20th Century. There is an example in the museum in Drogheda. There is also an early trade union banner (they have quite a collection) which features a coracle in the background. A photo from 1935 of an active Boyne coracle can be seen here http://ivrlaprod.ucd.ie/fedora/get/ivrla10-:10315/ivrla10-:objLayoutbDef/getLayout/

As far as I know there were/are a whole host of curraghs and coracles in Ireland, each region having its own variation, as can be seen here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Currach . The Aran Islands currach is very much the “archetype” image Irish people have a currach.

Yes I think there are still examples around. THanks for the links I will take a look.