A world turned upside down!

The 1640s are the decade when England would be torn apart by a Civil War which would kill a higher % of its population than even the first and the second world war. A king would fall and by the end of the decade the nation was a republic. It was a world turned upside down as a popular ballad of the day put it.

At the start of the decade the strongest and closest of Charles’ supporters were William Laud -Arch Bishop of Canterbury – and Thomas Wentworth (shown above) – appointed Earl of Strafford by Charles. Both were advocates of the Divine Right of Kings and of absolute rule. These concepts were now an anathema to the Paliamentarian forces that were growing and to whom Charles was now forced to turn for funds.

The Second Bishop’s War and the Short Parliament

There had been no lasting peace and settlement between Charles and the Presbyterian Scots – the Covenanters who opposed Charles efforts to enforce English style churches and bishops on them. Both sides started to raise troops again and with the Scots poised to invade England, Charles desperately needed funds to build an army.

Charles called up both English and Irish parliaments in early 1640.  Under the control of Wentworth, the newly created Earl of Strafford, the Irish Parliament voted Charles a payment of £180,000 and undertook to raise an army of 9,000. The response of the English Parliament was far different. Anti-Royalist Parliamentary candidates were voted into the commons in large numbers and undertook a stubborn attitude. Strafford tried to negotiate a compromise whereby the king would give up the unpopular Ship Money tax in exchange for £650,000 . Parliament would not agree to a payment without radical reforms – which Charles and Strafford were totally unwilling to discuss. Charles dismissed the “Short Parliament” in May 1640 after just a month.

Meanwhile the Scot’s Covenanter army had captured Durham and Newcastle and was strongly poised to dominate all of Northern England. Without the funding to raise a substantial army, Charles turned to Stafford who at least had raised funds and troops and sent him north to confront the Scots. Unfortunately Stafford became ill with dysentery and with the English army, outnumbers and poorly equipped, Charles was forced to make peace. In the Treaty of Ripon, the Scots were paid £850 a day and continued to occupy northern England UNTIL a final peace was found.

With no choice, in November 1640, Charles summoned what was later to become known as the Long Parliament. Of the 490 or so members, 390 of them were opposed to him and only 90 or so were Royalist. This was not going to be easy.

The Long Parliament and the end for Strafford

Once assembled and in uncompromising mood, the Long Parliament immediately impeached Arch Bishop Laud for High Treason.

Next, Parliament under the leadership of John Pym (one of the members who Charles had arrested in 1628) went after the other of Charles’ supporters: Strafford. Accused of abusing his power in Ireland and involving Irish troops in English affairs, he was put on trial for High Treason and, although that case collapsed, in April Parliament forced through the bill of attainder which demanded Stafford be executed. Charles tried to save Stafford but with no support in Parliament he was obliged to allow the execution.

Parliament now embarked on a number of steps to reform government. In February 1641, fearful that the King would try and dissolve parliament it passed the Triennial Act which required that Parliament was to be summoned at least once every three years, and if King failed to do so, the members could assemble on their own. Later Charles had to agree to not dissolving parliament without its own consent. Further steps were taken -Ship money, fines in destraint of knighthood and forced loans were declared unlawful, monopolies were cut back severely. The Court of the Star Chamber which had been prosecuting religious dissenters was abolished and taxation put on a legal footing.

The mainly protestant and puritan parliament now turned to religion. Laws were passed attacking and undermining bishops – although these blocked in the House of Lords.

So far all this had been one sided. However through these months, Charles had managed to gain some concessions that improved his financial situation, helped him strengthen the army AND he managed to make peace with the Scotish Covenant by guaranteeing Presbyterianism.

Parliament moved forward with even more changes – finally reaching the line which Charles would not cross with the Grand Remonstrance in November 1641. This was a long list of grievances against the King, the Catholic Queen, Henrietta Maria and the Kings advisor’s. It painted a picture of a grand catholic conspiracy. It gave voice to the Parlaimentarian’s beliefs of the King being under the influence of a great Papist plot. The Commons passed the act but the Lord’s and the King Rejected it.

Charles, outraged by the attacks of Parliament took an armed party to the Commons to try and arrest Pym and other prominent members. Never before had a King gone to the Commons and tried to do this. The members managed to escape and the door to the chamber was shut in his face (still ceremonially done today when the Queen sends for the Commons to join her for the State opening of Parliament.) This failure was a political disaster as it pushed more members into the Parliamentarain camp.

The Irish Rebellion

In 1641 the Irish Gaelic, Catholic majority had risen rose up in rebellion against the English rule that Stratford had imposed. There was a massacre of protestants and the ensuing outrage in England ensured that Charles would have to act. However when in early 1642 he asked parliament for funds Parliament passed the Milita Act.

This act attempted to wrench control of the army from the king. This was a direct attack on the royal Prerogative. Kings controlled armies and waged wars. The House of Lords refused to pass the act. The King refused to give consent. Pym forced through the act via the Commons alone – a breach of the rules and laws of the land which requited assent of Commons, Lords and Monarch.

It’s War!

After the failure to arrest Pym and the other leaders of Parliament, Charles had left London in January 1642. The Ordnance Act of March was the final straw that convinced him that military action to suppress parliament was needed. In the summer of 1642 both the King and Parliament began raising troops. The Earl of Essex took command of Parliament’s troops. On the 22nd of  August 1642, Charles raised his standard at Nottingham and called for an army to join him. He set up his capital at Oxford and began making plans. With the Royalist army assembling in the Midlands, Essex took the Parliamentarian army that way.

The first conflicts of the English Civil war was about to begin.

The 1642 Campaign

The King, beginning with around 2000 men, raised more troops in the Midlands as he moved south west towards Shrewsbury. Shortly after the King had raised his standard at Nottingham, Essex led his army north into the Midlands and across into the Cotswolds. By September both Essex and the King had around 20,000 men and were in close proximity on either side of Worcester. A clash was inevitable. That first battle was at Powick Bridge on 23rd September when Price Rupert – the King’s nephew and cavalry commander – defeated a Parliamentarian cavalry force and showed that in the early war the Royalist had an edge in terms of cavalry forces.

After that first battle, the King decided to strike towards London and try and reach it before Essex could get back there. Essex responed my marching towards London as well. So it was that Essex finally brought his field army into the path of the Royalist army at the little village of Edgehill. There on 23 October 1642, the first major battle of the war was fought. Both the Royalists and Parliamentarians claimed it as a victory but in truth it was inconclusive. The armies moved apart again and there was a chance for Charles to reach London but he hesitated and by the time he did move that way Essex had again got in the way and at the battle of Turnham Green was able to prevent the King breaking though.

The year ended with Charles forced to withdraw to Oxford which would serve as his base for the remainder of the war.

1643

The war went well for the King in the early part of 1643. Firstly the Royalist forces won at Adwalton Moor gaining control of most of Yorkshire. Likewise there were victories in the west of England at Lansdowne and at Roundway Down which enabled Prince Rupert to take Bristol.

The turning point came in the autumn of 1643, Essex’s army broke the siege of Gloucester and then defeated the Royalist army at the First Battle of Newbury (20 September 1643) Â and then returned triumphantly to London. Other Parliamentarian forces won control of Lincoln.

Late in the year both sides turned to political maneuvering to gain an advantage in numbers. Charles  decided to negotiate a ceasefire in Ireland, freeing up English troops to return to England, while Parliament offered concessions to the Covenanter Scots in return for aid and assistance.

1644

With the new help of the Scots, Parliament won at Marston Moor (2 July 1644), gaining York and control of the north of England. This battle showed Oliver Cromwell’s potential as both a political and a military leader. Elsewhere the war went better for the King. The Battle of Lostwithiel in Cornwall, kept the King’s cause alive in the south-west of England whilst the inconclusive fight at Newbury (27 October 1644), was also encouraging for the Royalists.

1645

In 1645 Parliament decided to take decisive action to end the wat and passed the Self-denying Ordinance. All members of either House of Parliament agreed to lay down their commands. The Parliamentarian army was totally reorganised into the New Model Army under the command of Sir Thomas Fairfax and with the impressive Cromwell as his second-in-command.

This New Model Army showed its tactical superiority over the Royalists at the Battle of Naseby on 14 June and the Battle of Langport on 10 July. In these two battles Charles’ armies were annihilated.

The King attempted to consolidate a power base in the Midlands and although he was able to fortify Oxford, Leicester and Newark on Trent, with the loss of his field army and with his resources exhausted he was clearly losing the war .

1646-47

With the New Model Army closing in on him and with Oxford under siege, Charles decided to surrender to the Presbyterian Scottish army at Southwell in Nottinghamshire in May 1646. He had hoped he might be able to negotiate a peace with them but the Scots eventually handed him over to the English Parliament. With the King imprisoned, the First English Civil War was over.

Parliament did not really at first know what to do with Charles. There followed months of negotiations. In November 1647, Charles escaped from Hampton Court and fled to the Isle of Wight but found that the governor was sympahetic to Parliament and imprisoned him in Carisbrooke Castle. From Carisbrooke, Charles was however able to try to bargain with the various parties and on 26 Dec. 1647 he signed a secret treaty with the Scots under which in exchange for concession on religion they agreed to restore him to the throne. He sent out messages to his supporters and prepared an uprising to coincide with the Scottish invasion. Charles was betting everything on one last roll of the die.

1648 – The Second English Civil War

The King’s English supporters rose in rebellion in July 1648 and as agreed with Charles, the Scots invaded England. However Charles dice roll was a bad one for the uprisings were quickly suppressed and at the Battle of Preston the Scots were crushed by the New Model Army. The king had lost the chance to win his throne back and had turned Parliament even more against him.

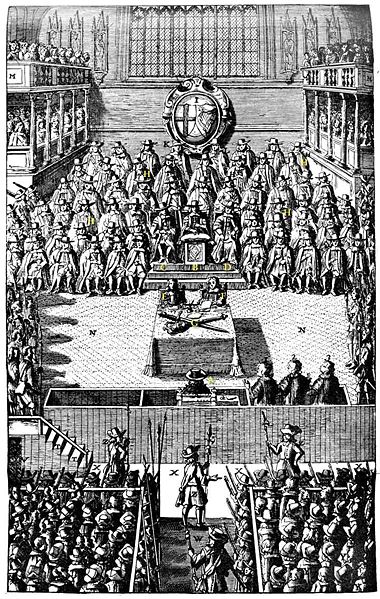

The Trial of A King

At the end of the First English Civil War many in Parliament were willing for Charles to remain king under a revised constitution. However by starting the Second War and in particular involving the Scots he lost much support in Parliament.. Nevertheless there was still reluctance to order a trial. A King of England had never been put on trial before. Kings had been murdered and deposed but not put on Trial. There was no real constitutional basis for such a trial.

The Parliamentarian Army under Cromwell felt very different. The Army marched on Parliament and evicted all but  75 Members from Parliament – the so called Rump Parliament. The Rump was ordered to set up the trial of Charles I for treason. The Trial involved much argument and Charles totally refused to accept its validity. To the end he maintained that he was answerable only to God. Found guilty of High Treason, his beheading took place on a scaffold in front of the Banqueting House of the Palace of Whitehall on 30 January 1649.

The Rump Parliament now ruled England BUT in effect was a puppet of the Army which was under the control of Cromwell. The 40’s drew to a close with Cromwell taking the Army to Ireland to suppress a Royalist/Catholic uprising without mercy. Like the slaughter of Protestants early in the Irish uprising against the rule of Thomas Wentworth this would colour how many Irish Catholics and Protestants felt about each other for generations – right down to the present day.

Next Week: No Christmas for you!! The Years of the Commonwealth.

Coming next week: 1650 to 1659

This article is one of a series connected with the release in August of the new paperback of The Last Seal my historical fantasy set during the Great Fire of 1666.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post